We rarely encounter health issues on our humble homestead, except those mundane ailments involving chiggers, poison ivy or ticks. Still, I enjoy adding to my library of old-time cures and concoctions ― just in case.

We rarely encounter health issues on our humble homestead, except those mundane ailments involving chiggers, poison ivy or ticks. Still, I enjoy adding to my library of old-time cures and concoctions ― just in case.

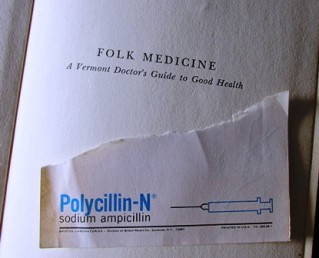

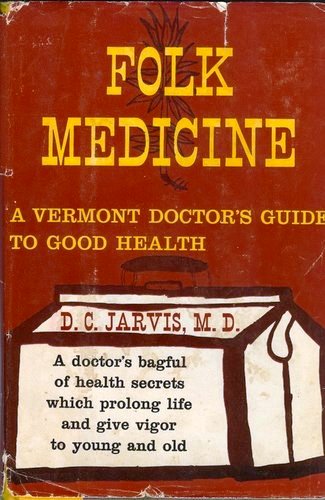

This summer, I was ecstatic to find a charming old book by a country doctor who believed it was imperative he study folk remedies to gain the medical confidence of his patients living close to the soil on back-road farms. Deforrest Clinton Jarvis, M.D., (1881-1966) wrote “Folk Medicine: A Vermont Doctor’s Guide to Good Health” at age 77 after spending decades gathering home cures that he said were as, or more, effective than those organized medicine taught him to use.

“I believe the doctor of the future will be a teacher as well as a physician,” Jarvis wrote. “His real job will be to teach people how to be healthy.”

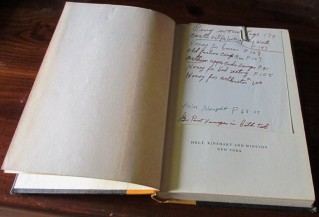

I especially love that my copy from a used book store has a penciled list of specific ailments paper-clipped inside, which leads me to envision a three- or four-generation household. The list includes: Honey for bedwetting, Page 105; Treating overweight, Page 68-69; Apple cider vinegar for arthritis, Page 91; and Castor oil for liver spots, Page 147.

I especially love that my copy from a used book store has a penciled list of specific ailments paper-clipped inside, which leads me to envision a three- or four-generation household. The list includes: Honey for bedwetting, Page 105; Treating overweight, Page 68-69; Apple cider vinegar for arthritis, Page 91; and Castor oil for liver spots, Page 147.

Inside, a homemade bookmark made of a torn slip from a medical pad advertising “Polycillin-N” is handwritten with “honeycomb treatment for sinus cold.” Did someone perhaps discard a physician’s prescription and instead found a natural remedy in this old book?

Jarvis is best known for advocating doses of honey and apple cider vinegar three times daily to prevent and/or cure many common illnesses including arthritis, rheumatism, asthma, high blood pressure and colds. The delightful elixir (one teaspoon each of honey and vinegar in a glass of water) also restores energy.

Already in 1958, Jarvis noted that our modern diet of fats, starches and nutrition-depleted processed foods made people sick, weak, overweight and listless. I wonder what he would think today of our synthetic and genetically modified foods laden with chemicals.

When he first began learning folk cures, Jarvis said many old-time treatments did not make medical sense to him, such as chewing the fresh gum of a spruce tree to cure a sore throat in a day. Jarvis’ further studies led to “considerable readjustment of orthodox approaches.”

The fifth-generation Vermonter not only sought the input of country folks for indigenous medicine, but studied insects, birds and animals to learn how they kept healthy. He watched wild and pastured animals to see what they ate and how they cured themselves when ill. Jarvis noted that humans are terrified to miss a meal, but animals know to retreat to a dark, secluded spot without food until they are well again.

“If you care to go to school, go to the honey bees, fowl, cats, dogs, goats, mink, calves, dairy cows, bulls and horses and allow them to teach you their ways,” Jarvis wrote.

Jarvis believed that everything people and animals need to survive could be found in nature. We hadn’t thought of it that way when we gave up buying commercially produced soaps and such. We simply wanted to avoid as many chemicals as possible. Now we use only all-natural stuff, such as our local Back Forty Soap Company’s goat milk soap.

Jarvis believed that everything people and animals need to survive could be found in nature. We hadn’t thought of it that way when we gave up buying commercially produced soaps and such. We simply wanted to avoid as many chemicals as possible. Now we use only all-natural stuff, such as our local Back Forty Soap Company’s goat milk soap.

Jarvis discovered that caged mink eating too much protein develop bladder problems and kidney stones, in many cases dying. But left to their own devices, wild mink supplement their carnivorous diet with berries and leaves. These same ailments plague humans eating a protein-rich diet. Eat more greens.

Farm children fascinated Jarvis, who discerned that children, like animals, have self-protective instincts about food. Studying Vermont children younger than 10, Jarvis discovered that these young children chewed cornstalks and ate potatoes, carrots, peas, string beans and rhubarb – all raw and fresh from the garden.

The youngsters also gobbled “berries, green apples, ripe apples, the grapes that grow wild throughout the state, sorrel, timothy grass heads, and the part of the timothy grass that grows underground. They ate salt from the cattle box, drank water from the cattle trough, chewed hay, ate calf food, and by the handful, a dairy-ration supplement containing seaweed; they even filled their pockets with this, to eat during school.”

Jarvis speculates adults have lost much of their natural intuition toward food and health. Probably more so today, we are influenced by such an avalanche of advertisements and advisements that we don’t even know what’s good for us anymore.

Jarvis speculates adults have lost much of their natural intuition toward food and health. Probably more so today, we are influenced by such an avalanche of advertisements and advisements that we don’t even know what’s good for us anymore.

“If we were wise enough to carry into adult life the instincts of childhood, we would make a point of eating fruit, berries, edible leaves, and edible roots that would not be cooked,” Jarvis wrote, adding that those who retained their natural impulses are fond of salads and are, consequently, healthier.

“Your body, designed for the living of primitive times, expects to receive a daily intake of leaves,” Jarvis wrote. “In these more civilized times the body still needs these leaves as much as ever, in order to better stand the stress and strain of modern living.”

Interviewing Vermonters who live close to the soil, he found many ate beechnut, maple, willow, apple, chokecherry, poplar and birch tree leaves. Elm tree leaves are said to be the best for quickly relieving hunger. Pages 48-55 list numerous wild edibles and their benefits.

Throughout the book, Jarvis gives examples of how honey and vinegar or a combination of both restored health to humans and animals. Not just any honey and vinegar will do, however. The honey must be raw (not pasteurized) and unfiltered, the darker and cloudier the better. Vinegar, too, should not be filtered or distilled. Processing destroys nutrients and beneficial bacteria.

My husband and I have been enjoying swigs of raw apple cider vinegar before each meal for more than five years. We fill our gallon jug with it at the local feed mill; we also buy local raw honey by the five-gallon pail. And, like I said, it has been years since either of us has had a cold or flu.

We’d never mixed honey and vinegar before, so I was eager to try it when I began reading Jarvis’ book. As I was visiting St. Paul, Minn., at the time, I walked 2 miles to the nearest health food store for some raw honey and vinegar and hurried back to my daughter’s apartment with the goods. I was immediately hooked on the delicious sweet and sour concoction, also known as switchel or honegar.

We’d never mixed honey and vinegar before, so I was eager to try it when I began reading Jarvis’ book. As I was visiting St. Paul, Minn., at the time, I walked 2 miles to the nearest health food store for some raw honey and vinegar and hurried back to my daughter’s apartment with the goods. I was immediately hooked on the delicious sweet and sour concoction, also known as switchel or honegar.

A quick search on Mother Earth News’ site revealed others who have followed Jarvis’ advice. In 1973, reader Sue Gross wrote to Mother Earth News in Feedback on How to Raise and Keep Goats to say how she fed vinegar to her goats, successfully curing mastitis. Also, author Laurie Masterson wrote of her mother serving honey and vinegar water with crushed ginger root to the field hands in this 2014 article, Switchel Recipe.

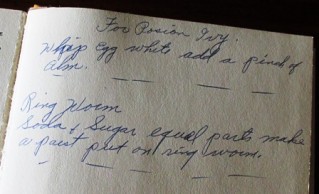

This handy book is available at ridiculously low prices on eBay, Amazon and other online sites for used books. It is not only fun to read, but could save a trip to the doctor’s office. I haven’t tried it yet, but I may even have found a cure for poison ivy penned in the back of this book.

This handy book is available at ridiculously low prices on eBay, Amazon and other online sites for used books. It is not only fun to read, but could save a trip to the doctor’s office. I haven’t tried it yet, but I may even have found a cure for poison ivy penned in the back of this book.

©2014 Well WaterBoy Products LLC ♦ WaterBuck Pump™ ♦ Pedal Powered PTO™